Todd, Laura, Lucy. From the sound of it, the two military veterans could be mentioning relatives or teammates. Yet their tone is more like that of teachers, recalling star pupils or the class clown who later shaped up. Charles, Dewey, Shannon.

All those named are indeed pupils — canine ones. They are service dogs in training, and the classroom is usually a field among farms in Boyds, Md. The students are Golden or Labrador Retrievers that are bred, trained, and placed by Warrior Canine Connection (WCC), a nonprofit organization serving veterans and military families.

The two veterans, both women, bonded with the dogs during research conducted by the University of Maryland School of Nursing (UMSON) in partnership with WCC. The study’s purpose is to understand how canine interaction, motivated by a desire to help other veterans, affects stress in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Ruck is responding to handler Susan W. Durham’s head in her hands, which is a stress cue response for the service dogs. The dogs are encouraged to escalate and break apart the veteran’s hands if the individual does not respond.

Ruck makes contact with handler Susan W. Durham’s hand to bring her back to the present moment after she had her head in her hands, a stress cue response for service dogs. The handler is then encouraged to praise and pet the dog.

All of the dogs at the Warrior Canine Connections are named for veterans. Siren, who is about 2 years old, is named in honor of Air Force Lt. Col. Vanessa “Siren” Mahan, who remains in the Reserves. She served at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan and became the first female Air Force Prowler aircrew assigned to a fleet carrier squadron.

Siren makes eye contact with Rick Yount, Warrior Canine Connections executive director, after name response was requested as Army Capt. (Ret.) JoAnn Krukar Webb watches. Yount is reinforcing the behavior with a food reward. This eye contact is an immediate response to the dog’s name being called and provided frequent enough to keep the dog connected with their handler.

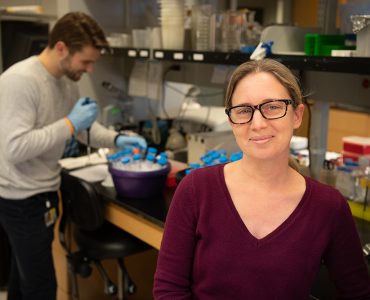

Principal Investigator Erika Friedmann, PhD, associate dean for research and professor at UMSON, seeks to establish the health impact by measuring physiological and post-traumatic stress symptoms of veterans enrolled in the study as trainers.

“A large number of veterans suffer from PTSD. It’s important to develop ways to help them that are complementary to other treatments,” says Friedmann, observing that individuals respond differently. “There are many modalities.”

Friedmann and collaborator Cheryl Krause-Parello, PhD, of Florida Atlantic University, are leaders in the field of anthrozoology, the study of human-animal interactions. They published evidence last year that dog walking affected stress indicators in veterans with PTSD and suggested further inquiry. Previously, in a 1995 study of heart patients, Friedmann found that pet ownership and social support are predictors of survival.

Friedmann’s latest study, “Evaluating the Efficacy of a Service Dog Training Program for Military Veterans with PTSD,” began in 2019 when UMSON received a $438,787 grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

So far 40 veterans have enrolled out of 60 expected to enter by early next year. Participants are paid for their time, and the research team follows strict COVID-19 pandemic safety protocols.

Eligible veterans are randomly assigned to one of two paths: an eight-week, online education course in service-dog training or eight weeks of hands-on dog training. They are encouraged to continue as volunteers with WCC, whose trainers expertly guide human-canine matchups.

For each group, researchers use surveys and biomarkers to assess impact. The dogs, too, see veterinarians to check well-being.

Veterans wear a device to measure heart rate variability and submit separate saliva samples. One sample gauges cellular aging; the other reveals levels of cortisol, a stress hormone.

JoAnn Krukar Webb, who recorded five years of active duty in the Army including serving in Vietnam, calls Siren “a real sweetheart.”

“I always left feeling better,” Susan W. Durham says of the training sessions that she and Webb, both veterans of the Vietnam War, complete together. “I would feel like we had a purpose. It was so fulfilling, doing what we’re doing. It made a difference in our mood.”

Susan W. Durham interacts with Ruck. Durham, who spent six years in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps on active duty and 24 years in the Reserves, is taking part in the School of Nursing study on the efficacy of service dog training for veterans with PTSD.

Siren, an almost 2-year-old black Lab, will go to a qualifying veteran and military family when training is complete.

Achieving Gender Balance in the Research

“Most studies of veterans are male-dominated,” says Friedmann, who disputes a myth that warfighters are the only ones traumatized by service. She notes that the UMSON study has achieved gender balance to date. “We’ve been able to recruit nurses and other female veterans.”

Among them are Lt. Col. (Ret.) Susan W. Durham, RN, MPH, PhD, who spent six years in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps on active duty and 24 years in the Reserves, and Army nurse veteran Capt. (Ret) JoAnn Krukar Webb, RN, MHA, FAAN, who recorded five years of active duty. Both served in Vietnam.

But the nurses talk less about their Vietnam War experiences and more about the rewards of dog training at WCC, where both are volunteer dog handlers. On this sunny October afternoon, Durham paired with Ruck, an 85-pound golden Lab, and Webb teamed with Siren, a smaller black Lab.

“A real sweetheart,” Webb calls her canine pupil, an enthusiastic dog who heeded Webb’s command to “settle.” Durham, meanwhile, was hooked by Ruck’s affable demeanor and steady pace.

“I always left feeling better,” Durham says of the training sessions that she and Webb completed together. “I would feel like we had a purpose. It was so fulfilling, doing what we’re doing. It made a difference in our mood.”

The appeal is greater knowing they performed at a key stage in each dog’s education. The regimen begins with a litter born and cared for at WCC headquarters. Puppies, most named to honor veterans, next spend up to 24 months with families. Back at Boyds, the maturing dogs are ready to interact with trainers such as Webb and Durham.

Then, deployment. Canine graduates go to qualifying veterans and military families nationwide.

Siren plays after training. All of the dogs see veterinarians to check their well-being during the study and training.

Siren and Ruck play after their training. The dogs at Warrior Canine Connections are all named for veterans. The names come by way of nomination, some from friends who served with the nominee and others from Gold Star families, spouses, children, and grandchildren.

Ruck, who is about 2 years old, is named in honor of Navy Rear Adm. Merrill W. Ruck, who passed away in 2019. His many assignments included commander, Naval Base San Francisco, and commander, Combat Logistics Group One.

‘Taking Care of Our Own’

WCC is a pioneer in training dogs to help veterans heal. “Bringing home praise and patience” is how one veteran described his experience to Rick Yount, MS, founder and executive director.

WCC’s model builds on a military core value: “Taking care of our own,” Yount says.

Friedmann also addresses the altruism factor. In their selflessness, the study’s dog trainers may benefit themselves. “They don’t feel like they’re being treated; they feel like they are helping others,” she says.

To enroll in the study, call 410-706-4233 or email dtaber@umaryland.edu.