The first time Larry S. Gibson met Thurgood Marshall, the Supreme Court justice was in his bathrobe. It was 1975 and Gibson, then an attorney, needed an order signed by Marshall. Gibson got lost finding Marshall’s Virginia home and arrived after 11 at night.

“The first words Thurgood Marshall ever spoke to me were, ‘Counselor, this better be a criminal matter,’ ” Gibson recalls with a chuckle.

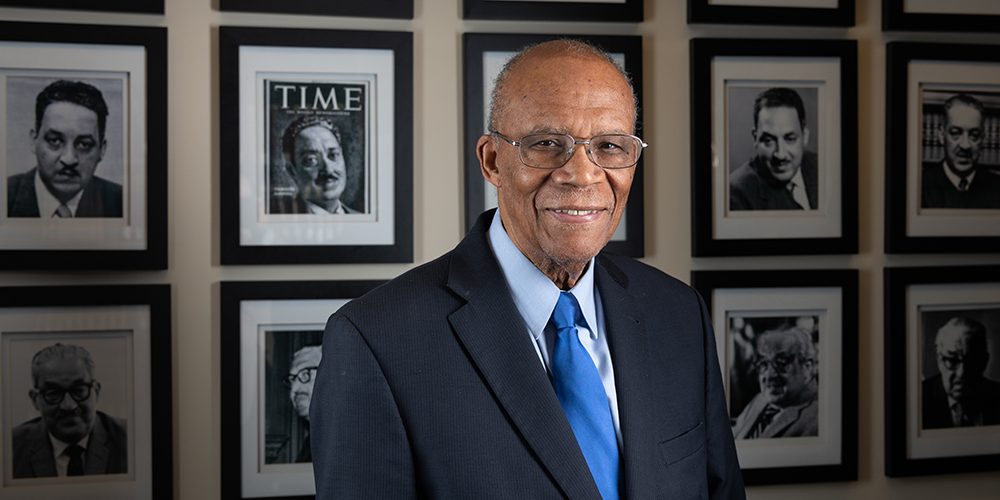

That evening Gibson, LLB, the Morton & Sophia Macht Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, stayed until the early hours of the morning talking with Marshall. As an African American who became an attorney in 1967 (the same year Marshall was appointed to the Supreme Court), Gibson always followed Marshall’s career. After that interaction at his home and another brief encounter at the dedication of the Baltimore City Circuit Courthouse, Gibson’s interest in Marshall the person was piqued.

“I decided then in earnest to learn more about this man and to capture people’s recollections about him,” Gibson says.

Gibson spent years gathering oral history accounts from Marshall’s family, classmates, and teachers. Through his research, Gibson realized that much of what was written about Marshall was incorrect. For example, Gibson says Marshall was not a poor student and late bloomer as many assert. On the contrary, Marshall was an adroit debater as early as high school.

Some inaccuracies were in print so long, they’d become part of Marshall mythology; others were perpetuated by Marshall himself, whom Gibson describes as a notorious “raconteur.” In 2002, Gibson published Young Thurgood: The Making of a Supreme Court Justice to set the record straight. The book was the culmination of Gibson’s primary source research and took 10 years to complete. That book ended in 1938 when Marshall became chief counsel for the NAACP.

Now Gibson is working on the companion volume, which will examine Marshall’s life from 1938 to 1954. Rather than format the book chronologically, Gibson tells Marshall’s story geographically with chapters on each of the Southern states where Marshall made an impact.

“It forces one to deal with the states individually instead of as ‘The South,’ ” Gibson explains. “The states become like characters in the book.”

With the first book, Gibson wanted to set the record straight. With the new book, Gibson shows Marshall’s character: his charisma, his diplomacy, and his empathy.

“I want people to understand not just what he did, but what he was like,” Gibson says.

“I want to show who he worked with, too, the Thurgood Marshalls of the states without whom he couldn’t have done this work,” he continues. “These are men who lived under constant threat of their lives, and [Marshall] was able to go there, build teams, and foster collaborations. He never demonized his opponents.”

The work on the book came as the country was focused on the nomination of a new Supreme Court justice, racial and social injustice, and COVID-19. The pandemic paused Gibson’s on-site research in various states, but he anticipates the book’s publication in 2021 or 2022.