School closures during COVID-19 have not just affected children’s learning and social development. A report issued by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers has found the pandemic decreased access to school meals, which is likely to increase the risk for food insecurity among children in Maryland.

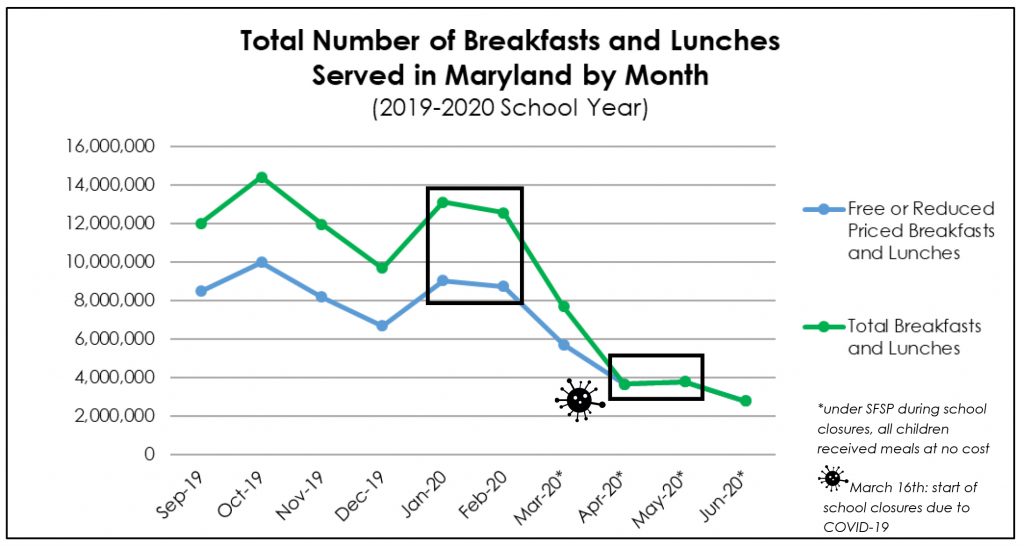

According to the study, the number of meals served to school-age children during the first three months of the pandemic dropped by 58 percent, compared to the number of free or reduced-price meals served the previous spring. As a result, thousands of children across the state were placed at increased risk of food insecurity, with many likely experiencing the health ramifications associated with the abrupt disruption in their access to regular meals.

“Food insecurity in children is associated with poor child health, low developmental and academic performance, and may co-occur with excess weight gain” because the children only have access to less-nutritional food, said study leader Erin Hager, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics and epidemiology and public health at UMSOM. “We found that despite the best efforts of food service providers across the state to ensure access to free meals during the pandemic, they were not able to reach every family in need. We need to learn more about what we can do to overcome these access challenges.”

Hager and her colleagues worked with the Maryland State Department of Education (which funded the study), local school systems in the state, and food service providers to evaluate meal distribution during the first three months of the pandemic.

Researchers interviewed 19 food service directors/supervisors and state leaders at two time points to capture implementation processes, including supportive factors for and barriers to pandemic school meal implementation. During this time, and even now, all meals distributed have been free to children under 18 years old. Hager’s team found that certain policies worked well to ensure access to free meals, including temporary waivers issued by federal and state governments to enable flexibility in policies normally in place to support subsidized meals.

For example, families did not have to prove that their incomes were below a certain level to gain access to the meals. They also could pick up multiple meals and multiple days of food for their children during a single excursion.

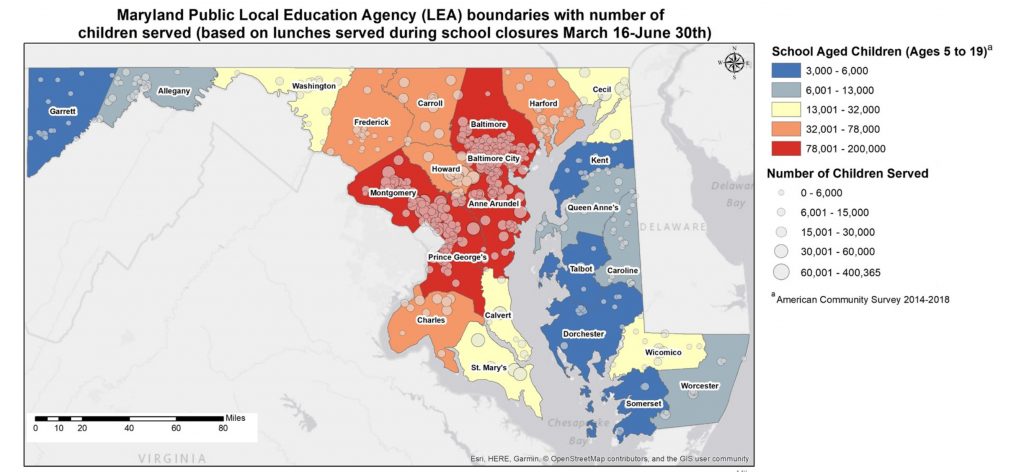

“Leaders of the school meal programs throughout the state chose to place meal distribution sites in areas where the need was greatest,” Hager said. The staff who worked at these meal distribution sites reported in surveys and interviews that they were deeply concerned about not reaching enough children in need and worried about children going hungry during the unprecedented school closures.

Financial resources remained a concern for the leaders of the meal program. After examining the financial data, the researchers concluded that, without significant local, state, and federal support, the financial health of these programs will take a major hit during the pandemic, when revenues are greatly reduced and expenses have grown.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the crisis of food insecurity in our nation’s children,” said UMSOM Dean E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, executive vice president for medical affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor. “We need to take a hard look at the lessons learned from this study to determine long-term solutions for providing meals to students when school is regularly not in session, including summer months and holidays.”