Bright lights shine in the operating theater. A trainee is observing, studying the surgery closely, but something on a nearby wall catches his attention.

“There was an old instruction sheet on the back door describing the collection of tumor samples for presumably radioimmunoassay testing to determine receptor status in breast cancer,” said Clement Adebamowo, BM, ChB, ScD, FWACS, FACS, who had been that curious surgical oncology student in the 1990s.

He asked his colleagues at University College Hospital in Nigeria about the instruction sheet because it seemed like someone had tried to set up a system for receptor testing in breast cancer — testing that could make treatment much more targeted and tolerable for women. But it wasn’t a practice that was widespread then, and he never discovered the instruction sheet’s origin.

“But it stuck in my mind,” he said. “As a surgical oncologist treating women with breast cancer in Nigeria, there were limitations imposed by not being able to characterize the type of breast cancer these women had.”

Decades later, Adebamowo, professor and director of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and associate director of population sciences at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCCC), is still thinking about this problem and how to solve it. In developed countries, a massive, expensive health care infrastructure enables this kind of cancer subtyping, where expert pathologists view tumor cells under a microscope and oncologists decide on the best treatment for each individual patient.

But in many low- and middle-income countries, this infrastructure doesn’t exist and the focus for investment is often on communicable infections, rather than diseases like cancer. Before moving to the United States, Adebamowo invested personal resources into developing a lab for this kind of testing in breast cancer, but now he’s looking to make a much larger impact.

Addressing Wait, Financial Impacts

At UMGCCC, Adebamowo has turned his focus to developing an invention that he says could change the cancer subtyping landscape in low- and middle-income countries.

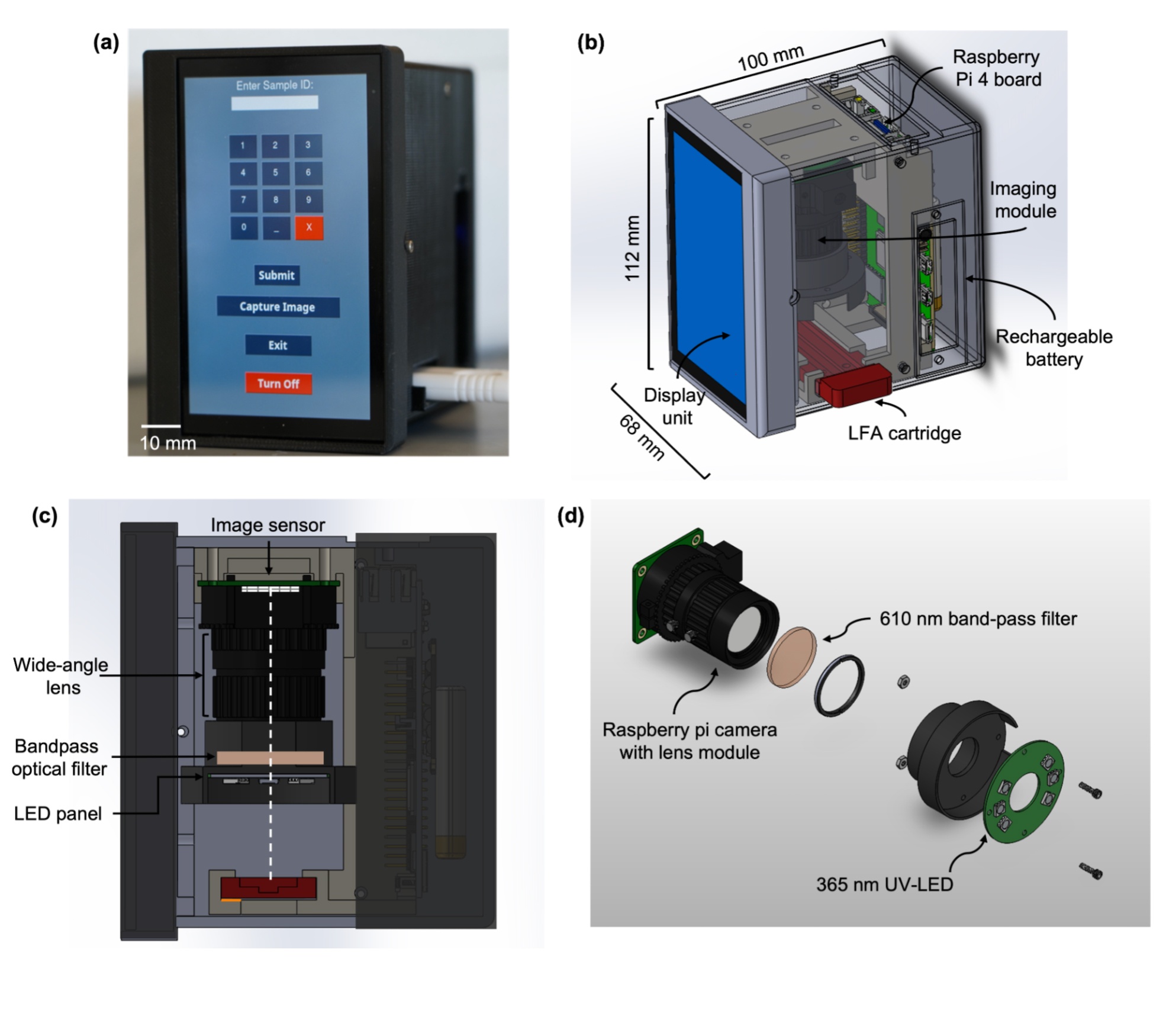

The prototype test, developed with the help of bioengineers, looks similar to an at-home COVID-19 test, the size of a thick glass slide you’d use under a microscope. A sample taken from the patient’s tumor is added to the sample well and diluted with a liquid phosphate saline buffer. The liquid travels up the test strip, with a red line appearing if it’s positive for certain proteins and continuing up the test strip where the control line will turn red.

The test looks for breast cancer-related receptors PR, ER, and HER2. This test is then run through a specialized machine that interprets the results. An oncologist can use this information to prescribe targeted therapy for the patient, whether chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, surgery, or radiation.

Without this receptor information, doctors may prescribe standard chemotherapy, which Adebamowo says can be expensive and have lasting adverse effects. But hormone therapy could be available to patients with certain protein receptors, which is much less expensive — $1 per month vs. $50 to $100 per month — and causes fewer side effects.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients stand to benefit from having access to this technology in different parts of the world,” he said.

Plus, it’s a rapid test, with results available in two hours compared to weeks or months with traditional testing. The prototype is also a cheaper alternative, and because it doesn’t require an expert pathologist to review the results, the tests can be deployed to areas without expensive health care infrastructure.

“I’m aware of how financially toxic a breast cancer diagnosis is for many patients,” Adebamowo said. “So, to be able to substantially reduce the financial impact on them would make me so excited and happy for them.”

Moving Beyond Prototype

Adebamowo is taking steps to move this beyond a prototype, with an application to patent the test toolkit and hopes of engaging a manufacturer who can produce the tests.

When he thinks back to his days as a surgical oncologist in Nigeria, eager to provide the best care possible to his patients, the idea of having a test like this at his disposal would have been a game-changer. “This would have been quite revolutionary,” he said.