Over hundreds of years, ships entering the Baltimore harbor have carried with them not only people and goods but also diseases.

Yellow fever was a particularly common epidemic in the 18th and 19th centuries in the port city of Baltimore. Because the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) is in the heart of the city, its students and faculty saw the firsthand effects of the disease, resulting in a long history of yellow fever research among those connected to the school.

For example, Dr. John B. Davidge, founder of UMSOM in 1807, published “A Treatise on Yellow Fever” after an epidemic in 1797. This paper became heavily cited on yellow fever and concluded that it was “indigenous, propagated by the atmosphere and non-contagious, merely a variety or aggravated form of ‘bilious remittent.’ ” In other words, yellow fever was caused by bad air. This theory of medicine was known as the miasma theory; it began in the fourth century with Hippocrates and prevailed into the 1880s when it was replaced by germ theory.

Contrarily, Baltimore doctor and UMSOM faculty member Dr. John Crawford theorized in 1790 that small particles or “animalcula” entered the human body and caused disease — an early form of germ theory. Because the miasma theory was well established, most doctors were highly critical of Crawford’s beliefs; he was forced to publish in non-medical periodicals. However, in 1848, Dr. Josiah C. Nott, a surgeon in Mobile, Ala., used Crawford’s theory and speculated that insects spread yellow fever in the article “On the Cause of Yellow Fever.” In 1881, Dr. Carlos Finlay of Cuba built on this work and discovered that a specific species of female mosquito spread the disease.

In 1898, Dr. Henry Rose Carter, an 1879 UMSOM graduate, working with the U.S. Public Health Service at a quarantine station at Ship Island, Miss., established the “intrinsic incubation theory” of yellow fever, positing that it took two weeks for the disease to incubate in the mosquito. In 1899, Carter, then assigned to Cuba, met Dr. Jesse Lazear, who began studying yellow fever while working at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1895. Carter shared his research results with Lazear.

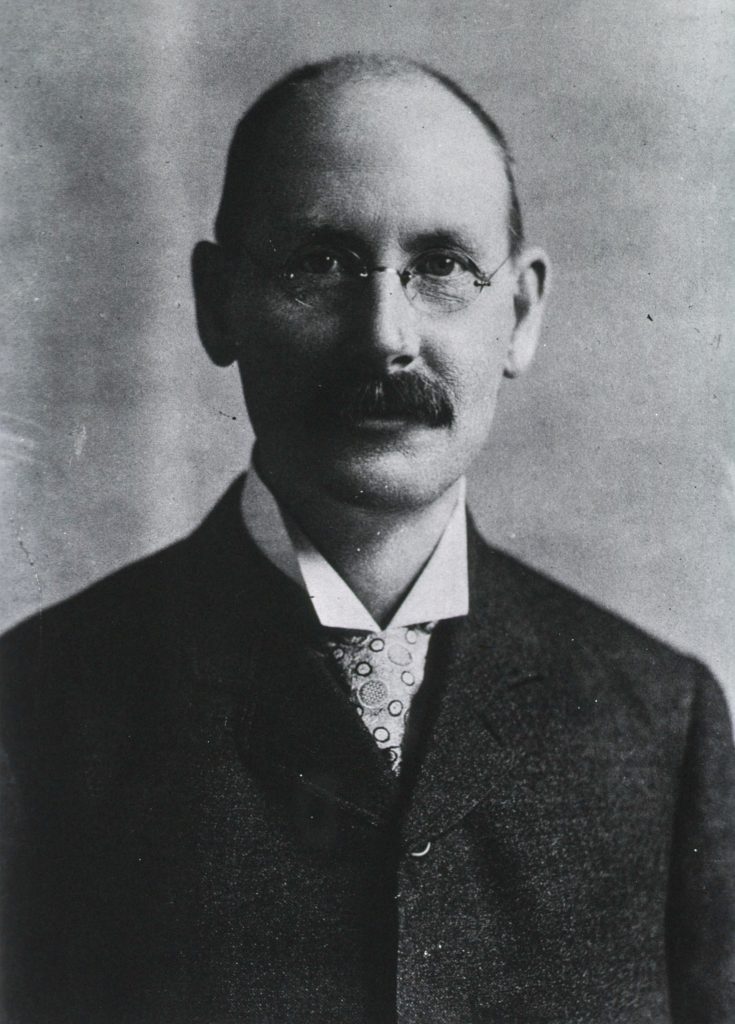

That same year, the U.S. Army, having lost hundreds to yellow fever in the Spanish-American War, established the Yellow Fever Commission, led by Dr. Walter Reed in Cuba. The commission included Lazear; Dr. Aristides Agramonte, acting assistant U.S. Army surgeon; and Dr. James Carroll, an 1891 UMSOM graduate who served as second in command.

The commission visited Finlay to learn about his theories and studies and was gifted mosquito larvae from him. Lazear hatched the larvae at the camp, had the mosquitoes feed on infected yellow fever patients, and then the team of doctors (minus Reed, who had returned to the United States) allowed the infected mosquitoes to bite human subjects including themselves.

Carroll was the first infected through a mosquito bite on Aug. 27, 1900. On Sept. 1, Carroll was transferred to the yellow fever ward with severe symptoms. Lazear and Agramonte sought additional verification that the mosquito caused the disease, so they subjected a private to a bite from the same mosquito. He became ill three days later. Through this, Lazear was able to confirm the incubation period that Carter theorized. Lazear, still feeling the need for additional data, infected himself with yellow fever on Sept. 13; within five days he became ill, and by Sept. 25, Lazear had died.

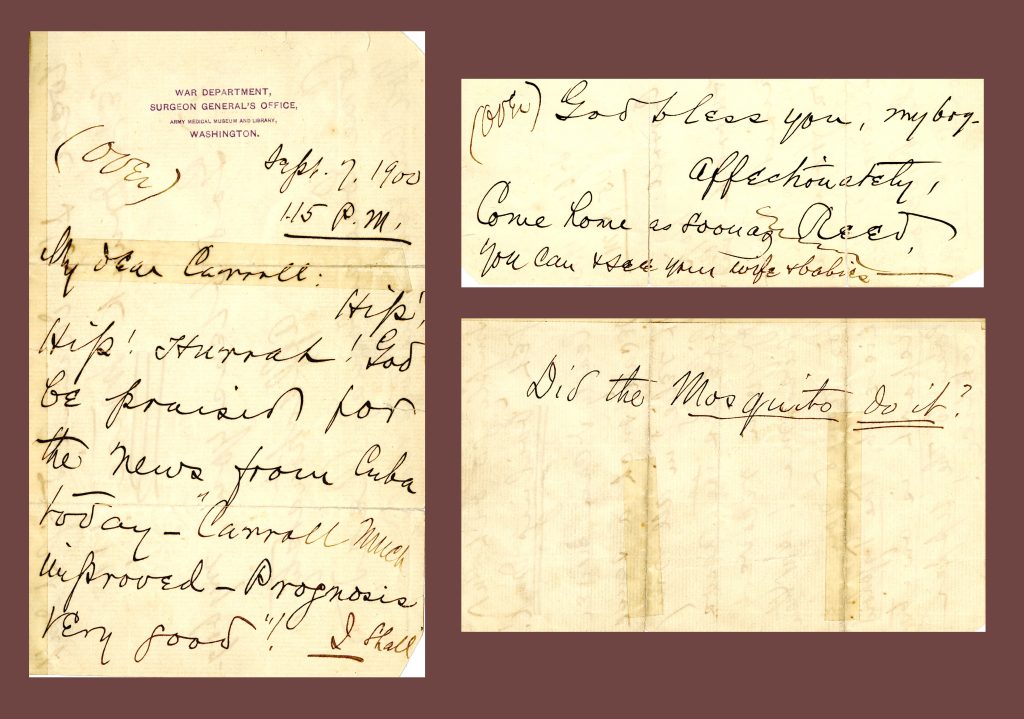

On Sept. 7, 1900, after hearing that Carroll was improving, Reed wrote him asking, “Did the Mosquito do it?” That letter is in a digitized collection of Carroll’s letters from the Yellow Fever Commission in Historical Collections at the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s Health Sciences and Human Services Library. The letters provide a glimpse of the relationship among the doctors in the commission, specifically Reed and Carroll.

Reed returned to Cuba on Oct. 6, 1900, to gather the notes of Lazear and the commission and returned to the United States. On Oct. 23, 1900, he delivered a report on the commission to the American Public Health Association. The report was published three days later in the Philadelphia Medical Journal.

Carroll and Reed returned to Cuba in August 1901, rejoining Agramonte, to do further tests on the causes and spread of yellow fever with funding from Gen. Leonard Wood, military governor of Cuba. The testing at Camp Lazear, named in honor of Dr. Lazear, was more rigorous and systematized due to questions surrounding the methods of the 1900 study.

The studies conducted in 1900 and 1901 by the Yellow Fever Commission concluded that yellow fever was carried by mosquitoes. These studies and the previous work done by Carter and Finlay ultimately led to a deeper understanding of the disease and paved the way for the prevention of yellow fever. Today, the disease is rare in the United States.