About 110,000 Americans are currently waiting for an organ transplant, and more than 6,000 patients die each year before receiving one, according to the federal government’s organdonor.gov. Faculty at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) are working to solve the organ shortage crisis by transplanting animal organs (known as xenotransplantation), which could potentially save thousands of lives.

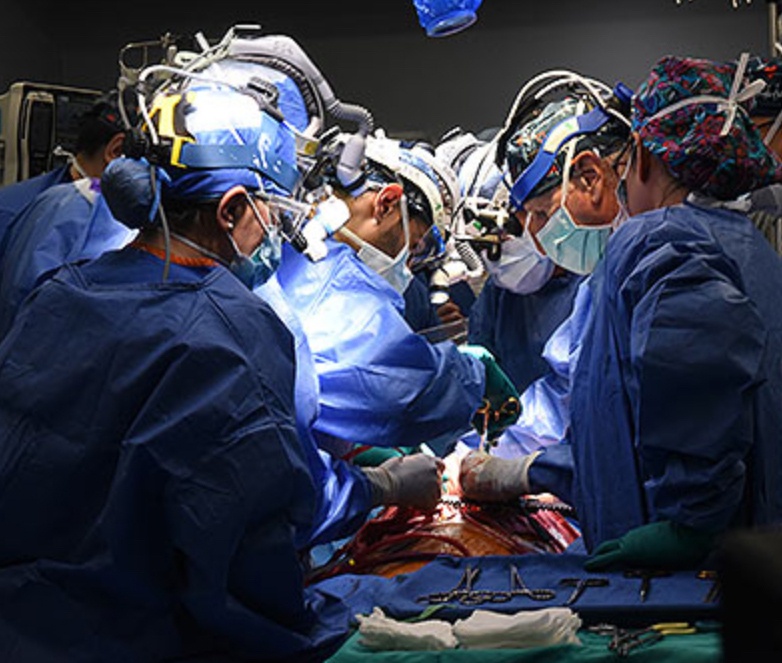

This fall, UMSOM faculty at the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) transplanted a genetically modified pig heart into a 58-year-old patient, the second time they have performed the historic surgery.

“As a cardiothoracic surgeon who does lung transplants, I am so grateful to our team of surgeons who are working to help solve the organ shortage crisis,” said Christine Lau, MD, MBA, the Dr. Robert W. Buxton Professor and chair of the Department of Surgery at UMSOM and surgeon-in-chief at UMMC. “Once again, we are at the forefront of a historic accomplishment that brings us one step closer to making xenotransplantation a lifesaving reality for patients in need.”

The patient, Lawrence Faucette of Frederick, Md., survived for nearly six weeks after the surgery, which was conducted by University of Maryland Medicine surgeons (comprising UMSOM and UMMC) who are recognized as the leaders in cardiac xenotransplantation. David Bennett Sr. was the patient of the first historic surgery, performed in January 2022.

UMSOM said Faucette’s heart began to show signs of rejection.

“Mr. Faucette had made significant progress after his surgery, engaging in physical therapy, spending time with family members, and playing cards with his wife, Ann,” UMSOM said in a statement. “In recent days, his heart began to show initial signs of rejection — the most significant challenge with traditional transplants involving human organs as well.”

“Mr. Faucette was a scientist who not only read and interpreted his own biopsies but who understood the important contribution he was making in advancing this field,” Mohiuddin said. “As with the first patient, David Bennett Sr., we intend to conduct an extensive analysis to identify factors that can be prevented in future transplants; this will allow us to continue to move forward and educate our colleagues in the field on our experience.”

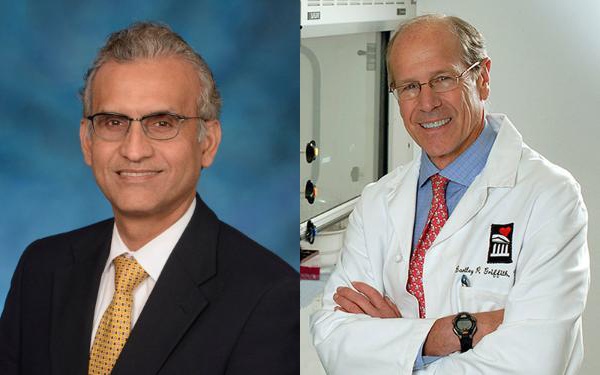

Bartley P. Griffith, MD, the Thomas E. and Alice Marie Hales Distinguished Professor in Transplant Surgery and clinical director of the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program at UMSOM, and Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, professor of surgery at UMSOM who is considered one of the world’s foremost experts on xenotransplantation, co-led Faucette’s procedure. Both expressed gratitude to Faucette and his family.

“Mr. Faucette’s last wish was for us to make the most of what we have learned from our experience, so others may be guaranteed a chance for a new heart when a human organ is unavailable,” Griffith said. “He then told the team of doctors and nurses who gathered around him that he loved us. We will miss him tremendously.”

Faucette was a man who always thought of others, said his wife.

“Larry started this journey with an open mind and complete confidence in Dr. Griffith and his staff,” Ann Faucette said in a statement. “He knew his time with us was short, and this was his last chance to do for others. He never imagined he would survive as long as he did or provide as much data to the xenotransplant program.

“He was not only thinking about how this journey was helping to advance the xenotransplant program, but how it affected his family. An example is his last night when he was lying in the bed contemplating the end and worrying about his sister and if she had slept yet. Larry’s family continues to be in awe of the man that he was and how he has shaped our lives. He can never be forgotten.”

The transplant was the only option available for Faucette, who had end-stage heart disease and was facing near-certain death from heart failure. Faucette was deemed ineligible for a traditional transplant with a human heart by UMMC and several other leading transplant hospitals due to his pre-existing peripheral vascular disease and complications with internal bleeding. He was a married father of two and a 20-year Navy veteran and most recently worked as a lab technician at the National Institutes of Health before his retirement.

“My only real hope left is to go with the pig heart, the xenotransplant,” Faucette said during an interview from his hospital room a few days before his surgery Sept. 20. “The entire staff have been incredible, but nobody knows from this point forward. At least now I have hope, and I have a chance.”

Added Ann Faucette before the surgery: “We have no expectations other than hoping for more time together.”

Emergency Approval Granted

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency approval for the surgery Sept. 15, through its single patient investigational new drug (IND) “compassionate use” pathway. This approval process is used when an experimental medical product, in this case the genetically modified pig’s heart, is the only option available for a patient faced with a serious or life-threatening medical condition. The approval was granted in the hope of saving the patient’s life.

“We are once again offering a dying patient a shot at a longer life, and we are incredibly grateful to Mr. Faucette for his bravery and willingness to help advance our knowledge of this field,” Griffith said.

Mohiuddin joined the UMSOM faculty seven years ago and established the Cardiac Xenotransplantation Program, where he serves as its program/scientific director.

“We are continuing to pursue the pathway to clinical trials by providing important new data on preclinical research that has been requested by the FDA,” Mohiuddin said. “The FDA used our data from these new studies, as well as our experience with the first patient, to determine that we were ready to attempt a second transplant in an end-stage heart disease patient who had no other treatment options.”

Solving Organ Shortage Crisis

Xenotransplantation potentially could save thousands of lives but carries a unique set of risks. Besides the fear of transmitting an unknown pathogen from the animal to the human, xenotransplants are more likely to trigger a dangerous immune response. These responses can trigger an immediate rejection of the organ with a potentially deadly outcome for the patient.

United Therapeutics Corp., through its xenotransplantation subsidiary Revivicor, based in Blacksburg, Va., provided the genetically modified pig to the xenotransplantation laboratory at UMSOM. On the morning of the transplant surgery, the surgical team, led by Griffith and Mohiuddin, removed the pig’s heart and placed it in the XVIVO Heart Box, a machine perfusion device, to keep the heart preserved until surgery.

The physician-scientists treated the patient with a novel antibody therapy along with conventional anti-rejection drugs, which are designed to suppress the immune system and prevent the body from damaging or rejecting the foreign organ. The novel therapy being developed by Eledon Pharmaceuticals is an experimental antibody, called tegoprubart, that blocks CD154, a protein involved in immune system activation.

Before consenting to receive the transplant, Faucette was fully informed of the procedure’s risks and that the procedure was experimental with unknown risks and benefits. He was admitted to UMMC on Sept. 14, after experiencing complications from his heart failure and peripheral vascular disease. Faucette underwent a psychiatric evaluation and met with a medical ethicist, social workers, and other members of the UMMC care team to discuss the procedure’s risks and benefits and to obtain his informed consent.

“This innovative program embodies the future of molecular medicine in surgery and speaks to a possible future where organs may be available to all patients,” said UMSOM Dean Mark Gladwin, MD, who also is vice president for medical affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor at UMSOM. “We recognize a heroic partnership with Mr. Faucette and his family, as we partner to advance the field of transplantation medicine into the next era. I appreciate the hard work of so many of our clinical, research, and administrative teams at University of Maryland Medicine. They have worked so hard over the last year to prepare for this day, doing everything possible to optimize the outcome of this historic surgery.”

Remarkable Achievement

“This transplant is another remarkable achievement for medicine and humanity that would not have been possible without the close relationship between the University of Maryland Medical Center and our University of Maryland School of Medicine partners,” said Bert W. O’Malley, MD, president and CEO of UMMC. “The Faucettes and thousands of families like them are the reason we are pressing onward to propel the xenotransplantation field forward. We are immensely proud to have taken another significant leap toward a day when more people who need a lifesaving organ transplant can get one.”

Organs from genetically modified pigs have been the focus of much of the research in xenotransplantation, in part because of physiologic similarities between pigs and human and nonhuman primates. United Therapeutics has funded a $22 million research program to test their genetically modified pig hearts from Revivicor in baboon studies conducted at UMSOM.

Three genes — responsible for a rapid antibody-mediated rejection of pig organs by humans — were “knocked out” in the donor pig. Six human genes responsible for immune acceptance of the pig heart were inserted into the genome. One additional gene in the pig was knocked out to prevent excessive growth of the pig heart tissue, for a total of 10 unique gene edits made in the donor pig.

During the nearly two years since the first surgery, UMSOM faculty-scientists have extensively investigated Bennett’s experience with the world’s first genetically modified cardiac xenotransplant. They published their initial findings in The New England Journal of Medicine and published their follow-up findings from an extensive investigation in The Lancet. They demonstrated that the pig heart functioned well in the patient for several weeks with no signs of acute rejection. Bennett’s death from heart failure was likely caused by a multitude of factors including his poor state of health that left him hospitalized on a heart-lung bypass machine for six weeks before the transplant.

Before performing the first surgery on Bennett in 2022, Mohiuddin, Griffith, and their research team spent five years perfecting the surgical technique on nonhuman primates. Mohiuddin’s xenotransplant research experience spans over 30 years, during which time he demonstrated in peer-reviewed research that a genetically modified pig’s heart can function when placed in the abdomen for as long as three years.