Celebrating its 200th year in 2024, the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law has emphasized an enduring commitment to excellence in education, scholarship, and public service; groundbreaking work on the integration of theory and practice; and a movement toward a more inclusive society within and beyond its walls. As we look back on its history, the school continues to demonstrate commitment to transcendent innovation in legal education.

One of the First Law Schools in the U.S.

In the early decades of the 19th century, the United States was in its infancy, with borders yet to be cemented and a system of government many considered experimental. American legal education, which largely consisted of apprenticeships and “reading law” independently, also was in its infancy.

As demand for legal services in the United States increased, universities began adding law faculty. In 1814, the same year the British attacked Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, the University of Maryland hired its first professor of law — prominent Maryland bar member David Hoffman. One of the first in the country to pen a curriculum and lectures for “law learning,” Hoffman went on to be the founding dean (1823-1836) of the Maryland Law Institute, which opened for regular evening instruction on Baltimore’s South Street in 1824. The Maryland Law Institute — as Maryland Carey Law was first known — is considered the fourth-oldest law school in the United States. By 1831, the student body had grown to about 30, and the institute moved to Courtland Street in 1833 to be closer to the courts. Moot court opportunities from the earliest days of instruction set a course for the school’s long history of leadership in the integration of theory and practice.

Reflecting its association with the university, the institute was renamed the University of Maryland, Department of Law in 1836 but temporarily shut down the same year until after the Civil War when it was reestablished as the University of Maryland, School of Law in 1869. Ten years later, the student body had grown to 60 and the faculty was made up of a who’s who of Maryland’s bench and bar with former Maryland Attorney General John Prentiss Poe (second cousin to author Edgar Allan Poe) as dean (1871-1909). In the late 1800s, the course of study went from a one- or two-year program to a required minimum of two years, illustrating the increasing stature of the legal profession and the expansion and complexity of discrete areas of the law.

Westminster Hall, adjacent to the law school, was built as a church in 1852 and is also a key part of the law school. Its cemetery is the resting place of Edgar Allan Poe and many other historical figures, including Founding Father James McHenry. In 1977, law school administrators led the establishment of the Westminster Historic Preservation Trust. This helped raise funding to refurbish the hall in 1983. Today, Westminster Hall is physically attached to Maryland Carey Law and serves as a gathering place for law school and private functions.

Confronting the Past

Notwithstanding the increased professionalization of legal education, the doors of the law school remained closed to everyone but white men until the second decade of the 20th century. The initial expansion was offered to white women who were allowed to enroll in 1920, with the first graduates in 1923. Black Americans and other people of color would have to wait longer for access.

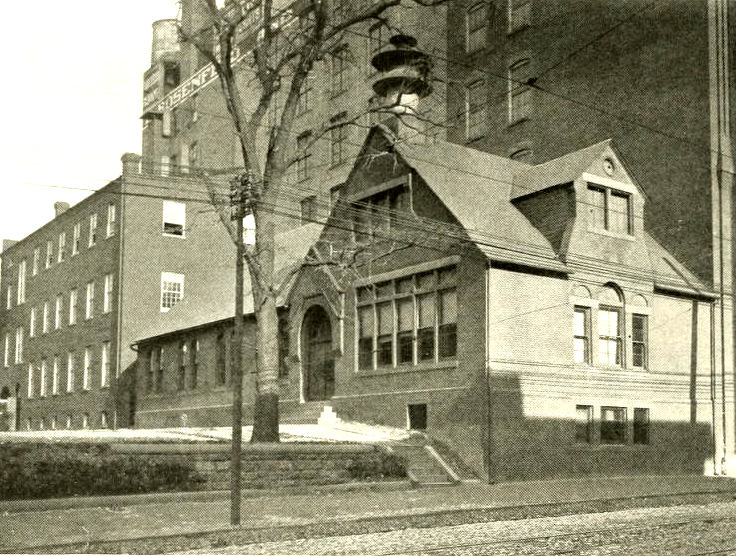

In 1925, the academic program expanded to include a day program to comply with American Bar Association standards. Enrollment continued to rise, and in 1931 the law school moved to a newly constructed three-story building with a library wing on the southeast corner of Redwood and Greene streets.

It would take another five years before anyone other than white people could take classes in the building. While the school allowed Black men to enroll in the aftermath of the Civil War, that practice was extinguished in the 1890s when John Prentiss Poe, now infamous for authoring legislation designed to disenfranchise Black voters in Maryland, was instrumental in resegregating the school with the backing of a petition from white law students. Finally, in 1936, Donald Gaines Murray ’38 was admitted, thanks to the tenacity of then-civil rights lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who, had he applied, would also have been denied admission because of his race. As Murray’s lawyer, Marshall successfully challenged Maryland’s practice of segregation in higher education in the landmark case Pearson et al. v. Murray. That same year, the Maryland Law Review, the only law journal in the state at the time, began publication.

Making Progress

The years to come would bring increased access to the legal academy for those who had previously been excluded. In 1946, Black women were allowed to enroll as law students, and in 1969, the first white woman joined the faculty. It would be another two decades before the first Black woman faculty member gained tenure status in 1989.

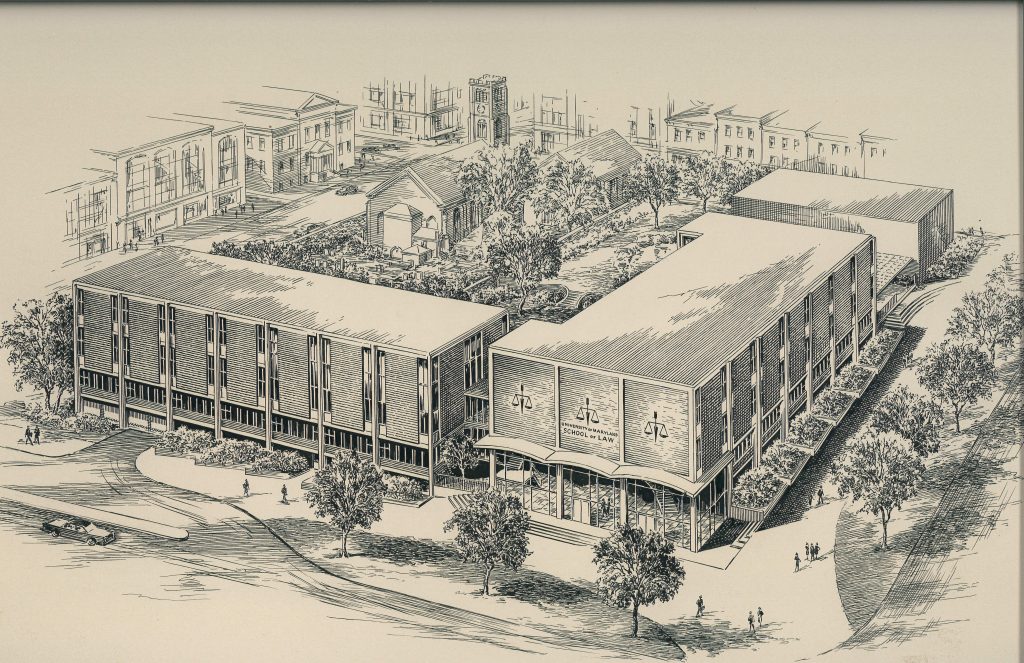

The law school moved locations again in 1965, when a new law school building was completed at Baltimore and Paca streets. The space accommodated about 550 students, 11 full-time faculty, and 50,000 library volumes. Chief Justice Earl Warren was the guest of honor at the opening celebration.

Charged by the civil rights and women’s rights movements, the student body and faculty began to diversify in earnest during the next decade, with the founding of the Black Law Students Association in 1968, the hiring of more faculty focused on civil rights, and a dramatic uptick in women applying to law school.

Just before the new millennium, the first woman dean, Professor Emeritus Karen Rothenberg (1999-2009), was appointed. Soon after, the law school moved into today’s modern law school building, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg offering the keynote address at the dedication. Professor Donald Gifford is credited with the initiation and much of the funding outreach for the new structure during his deanship (1992-1999). Rothenberg also secured funding, ensured that high-tech classrooms and reasonable accommodations were baked into the design, and completed the project.

Following the first woman dean was the first Black dean, Phoebe Haddon (2009-2014), and, in 2011, in recognition of a $30 million transformative gift from the W.P. Carey Foundation, the law school adopted its current name, the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, or Maryland Carey Law. The appellation honors Francis King Carey, an 1880 graduate and prominent founding member of two major Baltimore law firms.

Marshalling Excellence to Increase Impact

As early as the 1930s, law school students gained clinical experience working at the Baltimore Legal Aid Bureau. By the early 1970s, the school had a formal externship program with the Legal Aid Bureau and a grant-funded, in-house Juvenile Law Clinic. But under the leadership of Dean Michael Kelly (1975-1991), opportunities for students to apply, in a real-world practice setting, the legal theory they were learning in class multiplied and became one of the law school’s hallmarks. Other early clinics addressed legal issues around jail reform and civil rights, disability rights, housing, health, elder law, bankruptcy, consumer protection, environmental law, mediation, and AIDS.

A pivotal moment in the Clinical Law Program’s history came in 1987 when then-U.S. Rep. Ben Cardin ’67 and others led the charge for the Maryland General Assembly to allocate funds to expand the program and establish a Legal Theory and Practice component, which dramatically increased clinical options for students. The law school was one of the earliest adopters of clinic participation as a requirement for graduation, which became known as the “Cardin Requirement” in Maryland Carey Law’s curriculum. Now, many law schools across the country have followed suit.

The state funds enabled even more growth in the decades to follow with the launch or reinvigoration of clinics in areas including immigration, public health, tax, mediation, gender violence, juvenile justice, criminal appeals, post-conviction and sentencing, re-entry, and intellectual property. Others in the last five years alone include criminal defense, survivors of violence, appeals immigration, and eviction prevention.

Today, students, under faculty supervision, provide around 75,000 hours (or about eight-and-a-half years’ worth) of free legal services to disadvantaged and underrepresented communities in 17 clinics every year.

Along with a significant expansion of the Clinical Law Program in the 1980s and 1990s, the law school began offering specialized academic programs, many incorporating clinics, and some with the opportunity to earn a certificate.

Foreseeing the need for specialized legal expertise in the emerging field of health law, in 1984 the law school established the Law & Health Care Program, a perfect fit for a law school located on a health sciences campus as well as close to several federal health regulatory agencies. Early on, faculty in the program addressed issues such as end-of-life care, genetic testing, and access to emergency care. Soon thereafter, the pioneering Environmental Law Program was established in 1985. Its founding coincided with a rising awareness of the effects of pollution and climate change and anticipated the explosion in demand for lawyers trained in environmental law.

Multiple new programs and centers emerged during Rothenberg’s deanship in the 2000s, including one of Maryland Carey Law’s most innovative academic programs, the Women, Leadership & Equality Program, founded in 2002. The program provides a trailblazing curriculum that examines the structural barriers keeping women from ascending to positions of leadership in the legal profession. It equips students with the knowledge and skills to overcome and dismantle those barriers. At inception, the program was the first and only of its kind in the country.

The year 2002 also saw the founding of two high-impact centers: the Center for Dispute Resolution (C-DRUM) and the Center for Health and Homeland Security (CHHS).

The Center for Dispute Resolution trains students to navigate conflicts and solve problems in constructive ways and is a leader in developing and improving the quality of dispute resolution processes in Maryland’s courts, schools, workplaces, and communities. C-DRUM offers an academic track in dispute resolution, houses the Mediation Clinic, and trains Maryland public school educators and policymakers across the state in conflict resolution.

The Center for Health and Homeland Security houses a staff of more than 40 lawyers who work with emergency responders around the globe to develop plans, policies, and strategies for government, corporate, and institutional clients in the areas of emergency preparedness and crisis response. CHHS staff also teach in Maryland Carey Law’s Cybersecurity and Crisis Management Program in which law students specialize and gain experience as externs at the center.

Additionally, in the early 2000s, the law school launched the Legal Resource Center for Public Health Policy, providing technical legal assistance to Maryland state and local health officials, legislators, and organizations working in tobacco control. That work expanded dramatically, and in 2010, Maryland Carey Law became the home of the Network for Public Health Law-Eastern Region, which provides technical legal assistance to national, state, and local public health professionals, attorneys, legislators, and advocates working to develop sound public policy to improve public health.

In the late 1980s through the ’90s, the Business Law and Intellectual Property Law programs also were beginning to take shape, with the official founding of both in the early 2000s and a significant expansion of the Business Law Program in 2011 thanks to the transformative W.P. Carey Foundation gift. The Maryland Intellectual Property Legal Resource Center was founded in 2002 and laid the foundation for what would eventually become the Intellectual Property and Entrepreneurship Clinic in 2018.

To meet the demand for globally competent legal professionals, the law school in 2008 established the International and Comparative Law Program, which helps students understand the social, cultural, political, and economic factors that influence how the law is applied and offers study abroad opportunities in countries including Malawi and Ireland.

Envisioning the Future

With eyes toward the future, many of the law school’s recent efforts have focused on harnessing expertise and advocacy to expand community outreach and deepen work addressing society’s systemic inequities.

Under the leadership of Professor Donald Tobin during his deanship (2014-2022), the law school launched multiple new clinics, the Levitas Initiative for Sexual Violence Prevention, and, thanks to a transformative gift from Dr. Marco and Debbie Chacón, the Chacón Center for Immigrant Justice. The center, which builds on the expertise in Maryland Carey Law’s long-running Immigration Clinic, also includes a new Federal Appellate Clinic, which gives students additional opportunities to work directly with clients and advocate for law reform and policies to fundamentally improve the immigration system.

In 2023, the law school launched the Gibson-Banks Center for Race and the Law, which works to reimagine institutions and transform systems of racial and intersectional inequality, marginalization, and oppression. The center represents the law school’s vision and leadership in helping Maryland be a national model of re-envisioning systems and institutions to protect and improve the lives of everyone.

Carey Forward

The school is proud that its student body now typically comprises over 35 percent underrepresented minorities and exceeds 50 percent women. The faculty is also half women. A recent national study looking at the progress of women’s representation and achievement in American law schools between 1948 and 2021 found that Maryland Carey Law placed historically first for women’s representation among faculty and second for students.

Maryland Carey Law views diversity in the legal profession as an imperative. In the wake of the recent Supreme Court decision on affirmative action, the school remains committed to advancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in legal education and in the legal profession using the lawful tools available to it. Lawyers from diverse backgrounds bring unique perspectives and cultural insights that enrich the legal system, encourage innovation, and better serve clients from all walks of life. Presently, the legal profession falls far behind other professions in reflecting the diversity of the general population. The school believes it is its responsibility to ensure it is educating the next generation of lawyers with an eye toward closing that gap.

Dean Renée McDonald Hutchins, appointed in 2022, ushers in an era with increased emphasis, through scholarship and advocacy, on interrogating and reimagining the systems that perpetuate society’s inequalities. The start of Hutchins’ tenure also heralded a renewal of the school’s long dedication to nurturing a law school community, including 13,000-plus alumni, that prioritizes excellence in a welcoming and caring atmosphere. In the current climate, that means finding new ways to support students’ overall wellness as they face the mental health crisis that plagues our population. As the dean told this year’s incoming class, “We are a family.”

And the school is a family coming together with a vision. Maryland Carey Law is the state’s flagship law school, home to leading scholars and change makers. It is preparing the next generation of lawyers to lead with compassion and protect the rights of all people equally under the law, to use their access and power to build the American ideal that we still haven’t realized, and to craft policy that inch by inch will make our country a more perfect union.