Many Americans have a built-in support system they rely on when they give birth: grandparents who can help with the newborn and other grandkids, friends who can bring over meals and hold the baby. But what happens during a global pandemic when those supports might be unsafe? Rachel Blankstein Breman, PhD ’18, MPH, RN, assistant professor, University of Maryland School of Nursing, set out to find out what women have been experiencing during pregnancy and after childbirth, both in the hospital and at home.

Breman has found that our health care systems need to identify better ways to support the birthing and postpartum population. In a survey of women who gave birth between March 1 and June 11, 2020, women reported getting discharged as early as 24 hours after vaginal birth or 48 hours after a cesarean delivery because of COVID-19. Many of these women then found themselves at home with a new baby, often with other children to care for and without assistance from partners who had to return to work. Many survey respondents indicated that grandparents couldn’t offer support due to pandemic-related health risks.

“These women are isolated,” Breman says. “Many reported feeling anxiety, stress, loneliness, lack of support, and they talked about how they were unable to have help.”

Breman and colleagues also used other surveys conducted March 1 to May 27, 2020, of women who were pregnant during the pandemic to publish “Pregnant Women’s Reports of the Impact of COVID-19 on Pregnancy, Prenatal Care, and Infant Feeding Plans” in The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing.

In the surveys, women reported being worried about testing positive for COVID-19, having COVID-19 and passing it to their baby, and being separated from each other after birth (which the World Health Organization does not recommend). One mother in Georgia reported being separated from her twins after birth and being forbidden from seeing them in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for two weeks, missing important opportunities for bonding and breastfeeding.

Addressing Patient Needs

Although patients say they understand that the pandemic necessitates different approaches, health care providers still need to ensure that each patient’s needs are being addressed, Breman explains.

“A lot of it is about communication — making people aware of what the hospital policies are, finding out what these families need, and figuring out how can we be creative in achieving that during the COVID-19 pandemic,” she says.

Breman says providers also need to offer clear guidelines to new mothers. “Who is safe to come over and provide support to these new parents? They need it. They are already at risk for postpartum depression,” Breman explains.

This support could include a postpartum doula, a family member, or both if everyone follows COVID-19 prevention guidelines. New parent groups also have moved to online formats and could provide additional support as well.

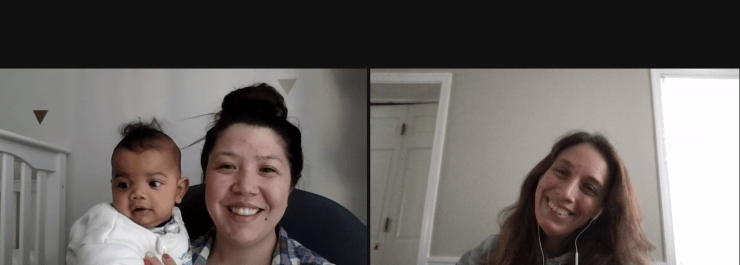

Breman’s work also considers how virtual visits can be improved. “Can we intervene earlier for postpartum support? If a new mother gets discharged early, can providers do a Zoom call on Day 3 instead of waiting two to six weeks?” she asks.

She recognizes the need for balance between keeping everyone safe during the pandemic and also providing patient-centered care that is really family-centered care. She indicates that family-centered care should involve both parents, such as including partners during prenatal care, during birth, in the NICU, and even at pediatric appointments for the newborns.

The next step for Breman’s research is exploring birth preferences, communication, and shared decision-making through the perinatal continuum. This work deepens the focus on supporting and advocating for pregnant women’s voices in their care during birth.

As Breman puts it, none of us would be here without safe motherhood.

“We should all care deeply about maternal health and reproductive justice at all levels,” she says.